Bumps II. Getting owned by "what works"

It looks like in an ideal world, bumps wouldn’t exist.

The silver medalist would be happier than the bronze medalist, free to savor being second best in the entire world. Billionaires who donate to charity would get more praise than those who don’t. A YouTuber who does something kind for entertainment would get less hate mail than when burning Lamborghinis, or whatever, for entertainment. Developers of free software would be copiously thanked. A public confession of wrongdoing would soften its hearers rather than sharpening their knives.

But we live in this world and bumps abound.

Maybe this is about what “works.”1 It might “work” to hate on Bill Gates in a way it won’t work to hate on billionaires who totally lack a social conscience. It often “works” to be deeply hurt when an intimate expresses something painful about you, in the sense of getting them to stop. It “works” for the athlete in training to focus single-mindedly on gold. But as soon as the competition ends, that entrained emotional strategy becomes a parasite on the joy and triumph that might very deservedly be enjoyed.

Scarily, these emotional programs might be easily installed but not as easily removed— at least, not without the right combination of ability/intent/support.

Again, importantly, this is often not a conscious decision. After a point, it may just feel like what the brain wants to do. It just wants to milk Gates.

Another example: people often feel spite for the weak, wanting to punish those who are easier to punish. Those who are more powerful and harder to punish can elicit respect.

This might feel foreign. But the mental motion of “I can [hurt them], therefore I want to” is just the even more pernicious flipside of the cognitive dissonance that leads to sour grapes: “I can’t, therefore I don’t want to.”

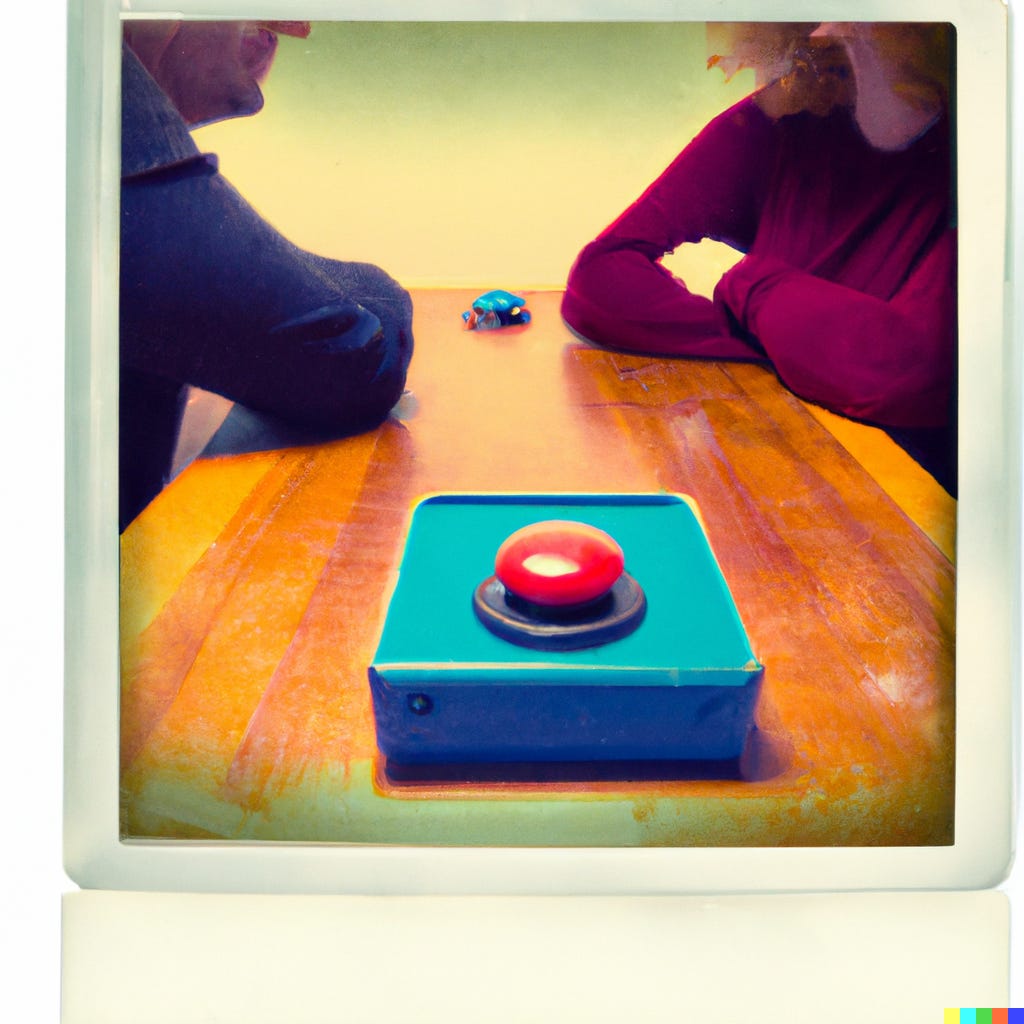

Like it or not, our desires are sensitive to our instinctive assessment of what’s possible, of which buttons feel pressable. The camel’s nose parable. Give them an inch and they’ll take a mile. This recognition has been in the commons for centuries.

An entire human body and will can be taken over just to press a button that feels pressable— and often won't be taken over for buttons that feel too hard to press.

Unconscious matters

Maybe you’ve had one of these moments. Something’s happened between you and another person and you feel deeply hurt. Your emotional arms are tightly crossed, eyes down. Suddenly, in a flash, it’s obvious to you that you’re sustaining this feeling. You want to punish the other person. Or soften them into sympathy. Or deflect attention from the way you were wrong. Your wounded dejection felt grippingly real a second before. Suddenly— and maybe for only an instant— you see that you’re manufacturing this state to do a job for you. While you see it, you have a choice that didn’t exist for you before.

For a strategy to work best, it can’t be conscious. The confusion about how you feel must go deep. If it's identifiable as voluntary, it doesn't work as well and might not work at all. If someone admits (even to themselves): "I’m not actually angry, I'm only angry because that's what I expect to work," the strategy is disarmed. It would be hard to stay angry if anger was fully recognized as instrumental. (Of course, depending on all sorts of things, a person might double down even harder on their strategy, churning out even more negative feelings to cancel or get away from what they just saw.) If a strategy is ever acknowledged aloud, it definitely won’t work. It stops being “real.” An otherwise forceful argument could dissolve in laughter.

Often we don’t glimpse our strategies at all.

For example, criticizing an intimate partner is a common strategy to change them. Over time, the person using the strategy just becomes more critical.

Expressions of insecurity evoke care and sympathy; over time, the actual experience of insecurity may happen more and more, since that is where care can be found. The person suffering insecurity is unlikely to guess they might be involved in generating it— with a deep invisible aim, almost as if there’s a conspiracy against resolution— because their partner’s reassurance is so rewarding.

Someone I know talks about the phenomenon of being unable to enjoy one’s own cooking. It is useful to put on a little Chef’s Hat while you’re making food. Taste the soup, add salt, try fish sauce, be critical. But once you sit down to eat, you want to be able to take the hat off! You have to see and exit your strategy to become the eater who enjoys the food.

Our strategies are at our sides yet we often never see their faces, maybe barely catch a shadow of their shape like a stranger on the street. Bumps don’t even seem like weird aberrations, they seem natural and obvious. We feel feelings, think thoughts and say sentences to try to change reality— all while thinking they are reality, that they innocently and truly map what is real.

So we see it’s incredibly easy to confuse

who you are with

your strategy to get what you want.

And this confusion is a prime way to undermine your own autonomy– and lose choice. When we confuse self with strategy, we no longer own our tools.

Instead, they own us.

Not to imply that there’s a single underlying explanation for every kind of bump.